Mary Michael Shelley: Serving up a Slice of Everyday Life

by Magaret Day Allen

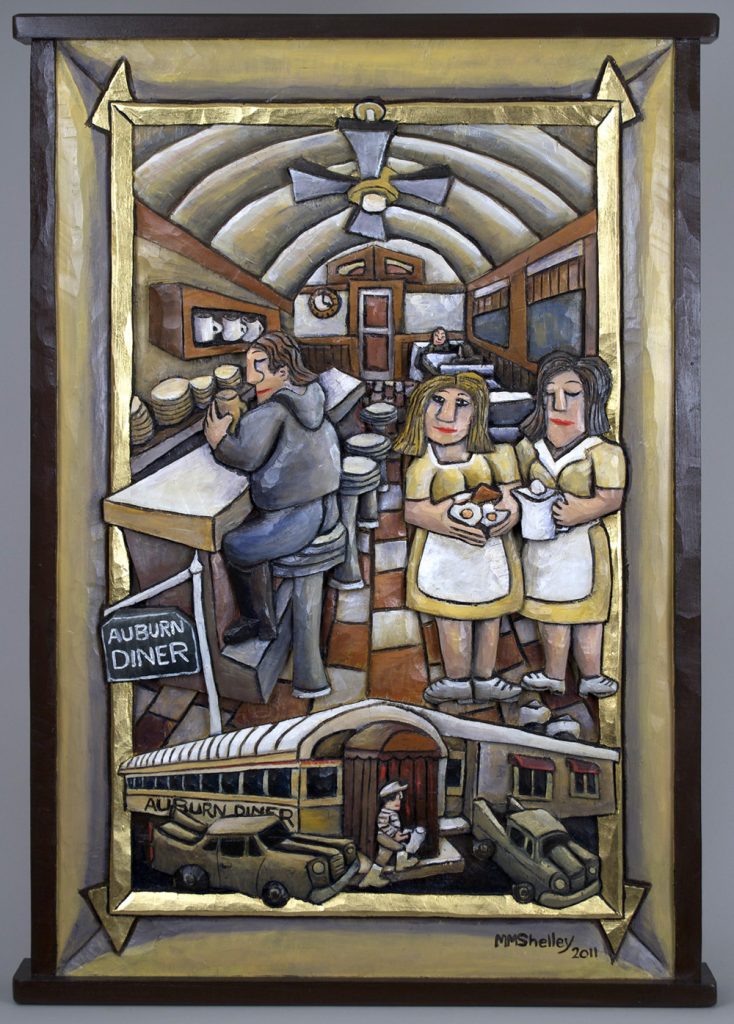

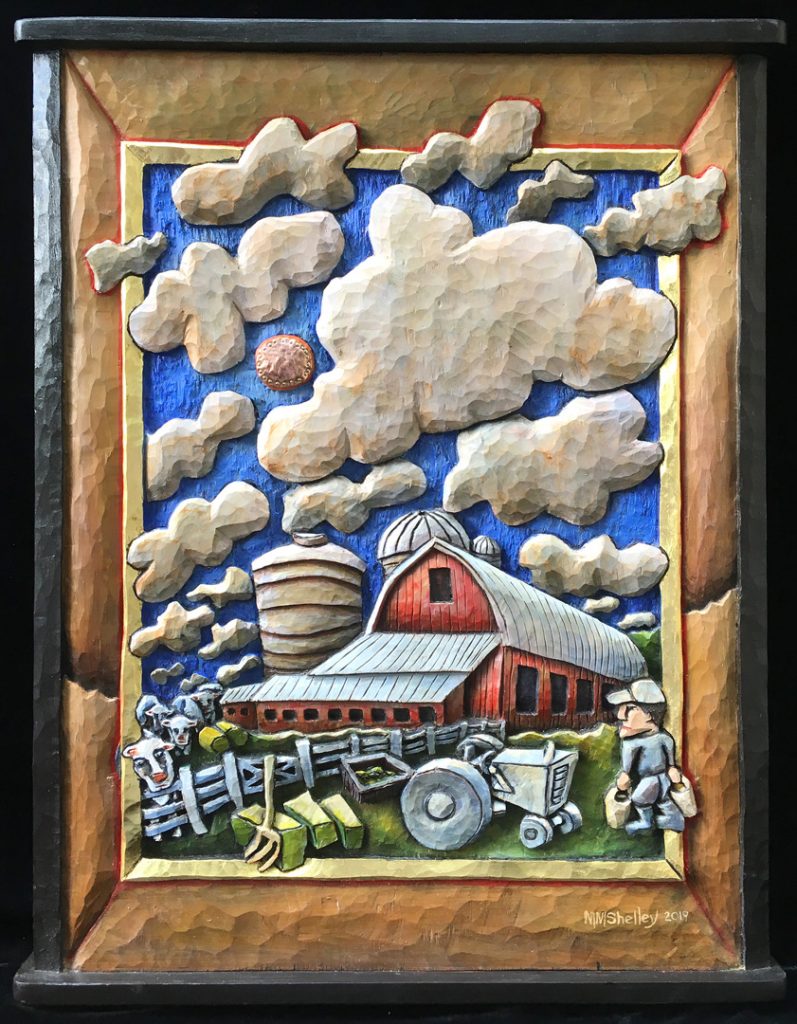

Woodcarver Mary Michael Shelley is perhaps best known for her scenes of weary waitresses and cows with mournful eyes. She sees them both as domestic creatures. Cows are dependent on the farmer who milks them. Waitresses are dependent upon the customer for tips. “They are all a little downtrodden, but also joyous,” she said. Perhaps that is why they resonate with so many people.

Shelley’s mother was one of the first women to graduate in animal husbandry from Cornell University. While there, she fell in love with a fellow student from New Jersey who was a talented artist. The two married and bought the farm near Doylestown, hoping to run a dairy farm. But by the time Mary was five, they had quit farming, and her father had begun working as a commercial artist, traveling from a home studio to jobs in New York City.

Shelley, who was born in 1950, has had plenty of opportunities to watch both cows and waitresses. As a child she lived on a former dairy farm about 15 minutes outside of Doylestown, Pa., with her parents and three brothers. The area is known as Pennsylvania Dutch country where many Mennonite people live. Her family is not Pennsylvania Dutch, but her mother’s parents once owned a dairy farm and ran a milk delivery service. However, their operation closed during World War II because there weren’t enough available men to serve as delivery drivers.

Mary grew up on the farm, owning a pet goat and a horse. At the time, there were many active dairies in the area, with trucks picking up milk once or twice a day. She enjoyed exploring the area, especially her parents’ and grandparents’ abandoned barns.

After high school, she also attended Cornell University, majoring in English. She wanted to be a writer, but since she didn’t want to teach, she had trouble finding a job after graduating in 1972. About that time, her father gave her a wooden plaque he had carved and painted showing her riding her horse at the farm where she grew up. It planted the seed for her future career as an artist.

She stayed in Ithaca, where Cornell is located, and went to work for Historic Ithaca helping to renovate Clinton House, an 1830s historical hotel. She desperately wanted to learn carpentry, but usually found herself relegated to sweeping up and spackling walls. She then decided to try woodcarving. After hours, she began carving and painting scenes of farm life, teaching herself the necessary skills. Over time, she realized that “making things” suited her personality more than creative writing. At first, it was hard to sell her painted woodcarvings. She even resorted to knocking on doors and offering to carve a picture of people’s houses. A few commissions came her way, and then people began asking her to carve wooden signs. Simultaneous to making her art, she worked as a sign carver for about 15 years, until computerized sign printing became common. She couldn’t compete with the new technology, so she refocused on her artistic carving.

In the 1980s, she and her longtime partner, Barbara, were busy raising their two children. Understanding the ups and downs of being a working artist, as well as the responsibilities of motherhood, Shelley always held down another job. In her 30s, she returned to college, earning a degree in social work from Syracuse University. She has had a private social work practice ever since, although now she is operating that practice only two days a week, while making art five days. “I’m pretty persistent as a person,” she said.

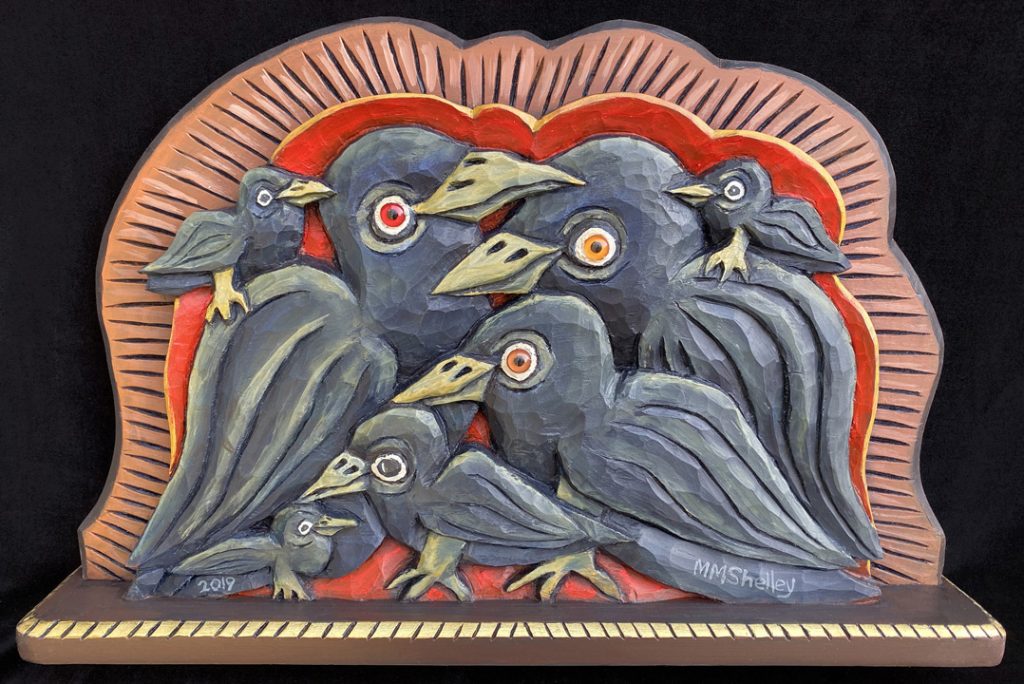

Her wooden artwork is carved from white pine, which she buys from a small local mill that will cut it in custom widths. She then takes it home and stacks it under her porch to air dry for about a year to stabilize the wood. She said air drying is better than kiln drying for long-term durability.

She also puts a brace on the back of the plaques to reduce the chances of cracking, although some movement is inevitable as wood naturally expands and contracts. Shelley uses a double-car garage behind the house as her studio. There she is free to spread out and leave a mess. She first cuts the wood into the desired shape with a band saw. Then she draws the scene and carves the details. She prefers hand tools, although she occasionally uses power tools for some of the work. After carving, she paints the scene with acrylic paints and often puts gold leaf along the inside edges. The gold leaf is left over from her sign-painting days. Being thrifty, she didn’t want it to go to waste. Sometimes she uses copper for highlights such as the sun, or even tacks to emphasize a part of the scene.

The size of her work varies, from smaller pieces that may only show a single person or animal, to elaborate scenes. “All my animals are a little humanoid,” she said. Shelley never duplicates a piece, although she sometimes creates a series of similar pieces as she works through an idea. She said she enjoys the process because it is meditative. “I am working all the time,” she said. She was formerly represented by America’s Folk Heritage gallery in New York City, but has sold her work directly since that gallery closed due to the death of the owner.

Every weekend in the summer, she carves and sells at the Ithaca Farmers Market. In the winter, she mostly paints the carved pieces at her home studio, although she also carves there.

She regularly posts to social media “because it’s a way to get out there.” She also sells online at her website, www.maryshelleyfolkart.com.

Some of her subjects are diners, farms, vacation/outdoors and dreaming. Pulling from her own experiences and observations, her art expresses the joys and challenges of a simple life. Many of the outdoor scenes show people fishing or sailing. Shelley says she fished with her father as a child and now enjoys sailing on nearby Cayuga Lake. She includes subtle references to her interest in environmentalism and women’s rights. “I like to have a layer of meanings, such as sailing, action, recreation and environmental. It’s not the only message I want to get across.”

Shelley said she was disappointed when the Equal Rights Amendment wasn’t ratified in the 1970s, and decided she was going to carve cows and waitresses until it became a part of the constitution, although now she carves many different subjects.

She estimates she has created 2,000 to 3,000 different pieces. Now nearing 70 in age, she finds herself thinking about her own mortality and looking for ways to reflect that in her work. Some of her recent pieces show a woman being swept away by the wind, or hats being blown off in the wind. Those pieces reflect on the unexpected events that shape our lives, she said.

From October 2019 through January 2020, a retrospective exhibit of Shelley’s art was shown by the New York Folklore Society in Schenectady, N.Y. Absolut Vodka commissioned a piece of her art called Absolut Barn Dance. An image of the piece appeared in a Country Home Magazine ad in 1990 and is in the Absolut Vodka Collection in New York City. Similarly, Coca Cola commissioned her to carve a piece for the 1996 Atlanta Olympics including the outline of a Coca Cola bottle. Her piece, which stands six feet tall, features a diner scene with people drinking Coca Cola. It is currently in the lobby of the World of Coca-Cola museum in Atlanta.

Other pieces of her art are in the permanent collections of the High Museum of Art in Atlanta; the American Folk Art Museum in New York City; the Fenimore Art Museum in Cooperstown, N.Y.; the American Museum in Bath, England; the National Museum of Women and the Arts in Washington, D.C.; and Women’s Rights National Historical Park, Seneca Falls, N.Y.

She carved and painted an egg that is in the Smithsonian’s White House Easter Egg Collection. In 1981, her work was included in the National Museum of American Art’s More than Land or Sky: Art from Appalachia exhibition, a show that later traveled through major cities in the 13 Appalachian Region states, 1982-84.

In 1999, the New York State Historical Association celebrated its centenary with a show of works in its permanent collection, including one by Shelley called “Sullivan’s Diner IV, Waiter Holding Fried Eggs.” A New York Times review of the exhibit said this: “If much of the 20th-century work in the show is fanciful, it also touches on real life in all its bumptious oddity and warmth. Such is the case with the painted relief [by Shelley]. The piece, which conjures up 19th century shop signs and the sculptures of the contemporary artist Red Grooms, depicts the interior of a local restaurant that Ms. Shelley frequents. She chose the subject, she says, because restaurants are places ‘where people, isolated during the rest of their day, could come together just to ‘be’ and feel a sense of instant belonging.’”

On her website, Shelley answers the question, “Why the waitress on my stationery and website?” this way: “She’s really me. She serves food with a smile on her face, even though her feet hurt. Artists serve food too, a different kind of food. For your information, my first job was as a waitress. In the 40 years I’ve been carving/painting, I’ve made perhaps 200 pictures of diners. After all that standing up and carving, now my feet hurt too.”

MARGARET DAY ALLEN is a member of the FASA National Advisory Board and the author of When the Spirit Speaks: Self-Taught Art of the South.