Carving Out a Life: Reflections of an Ithaca Wood-Carver

BY MARY MICHAEL SHELLEY

Reprinted with permission from Voices: The Journal of New York Folklore, Vol. 35:3-4, Fall/Winter 2009. Copyright 2009 by New York Folklore Society

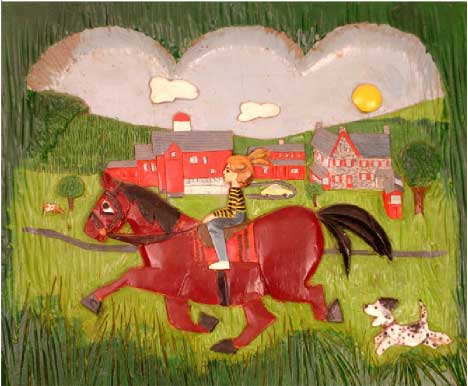

I was born in 1950 in Doylestown, Pennsylvania. I started carving at age twenty- two, when my father gave me a gift of a painted wood-carving he had made of me at the farm where I grew up. This gift from my father inspired me to begin to make my own carved and painted pictures. Since then I've made more than one thousand pieces in thirty-five years. I think of my pictures as a visual diary that helps me make sense of the events and feelings of my life.

I grew up on a 120-acre farm near Bed- minster, Pennsylvania. I had a horse named Admiral, a goat Nellie, and a dog Lulu. My mother graduated from Cornell in the 1940s, one of the few women in her class in the Ag School. My father-an artistic city boy from East Orange, New Jersey, whose family originally came from Rome, New York-also went to Cornell, where he was a cartoonist for the student paper and involved in acting and writing plays. After World War II, my mother and father decided to try to make a go of farming. They settled on a farm near my maternal grandparents.

My grandparents, Tom and Florence Shaw, had a dairy farm, complete with milk delivery trucks, in Doylestown in the late 1930s. I still have a metal cow sign that was at their farm and a glass milk bottle with the name of their dairy, Pebble Hill Farm. It was with the inten- tion of running their farm that my mother went to Cornell to study animal husbandry. But then the war came, and the dairy closed down because the milk delivery drivers were drafted. Farm equipment and animals were sold.

By the time I was five, my parents also to his true interests: he began working as a commercial artist, traveling back and forth between a home studio and his new work in New York City. So now our barn, like that of my grandparents, sat empty.

As a young child in the 1950s, I explored my parents' and grandparents' empty barns. I can still remember the echoing whitewashed walls, the empty stalls and stanchions, and wondering what it might have been like when there were animals and farmers and activity. I loved the cooing sounds of pigeons up in the eaves. Once when I went into the haymow of my grandparents' barn, a great white owl took off with a thunder of wings. I think those first few barns in my life filled me with a wonder for barns and their cathedral spaces.

Like my parents, I went to Cornell, want- ing at first to get a degree in psychology, but graduating in 1972 with a degree in English literature and creative writing. After graduation, I stayed in Ithaca and have remained here ever since. At Cornell, I had studied to be a writer. I never had any visual art train- ing, because I didn't feel I had artistic talent in that way. When I graduated, reality hit-I had to make a living. A course of events in my life took me toward becoming a visual artist.

It was the 1970s. There was a revival of interest in crafts and traditional skills. It was "back to the land," and I was a part of the times. I built my own passive solar house ten miles from Ithaca. My neighbors lived on communes, and most of my long-term friends come from these times. In the mid-1970s, the country was trying to pass the Equal Rights Amendment, which would have mentioned women in the constitution. It didn't pass. Women were breaking out of the traditional roles of the 1950s, and moving into new occupations. I took pride in being a part of that movement.

When I graduated from Cornell in 1972, I worked with a local historical society, Historic Ithaca. We were renovating the Clinton House, an 1830 hundred-room Greek Revival hotel in downtown Ithaca. I was desperate to learn carpentry skills, but I kept getting stuck with sweeping and painting. I wanted to learn carpentry because it seemed more interesting and involved more skill, but also because it was better paid than the grunt work I was doing. On one of my father's visits, he had picked up a wide, aged shelf board thrown out in the renovation of the hotel. It was on this scavenged board that he carved "Me on Horse at Bedminster Farm." When my father sent me the painted carving, I jumped into carving as a way of getting my hands on wood.

When I began to carve he advised that I use one of the same shelf boards, which turned out to be white pine. Luckily, white pine is a good carving wood, because if I had chosen a harder wood such as oak, perhaps I would soon have given up. I thank my father for that. He also advised that I start out using Exacto knives, because this way I wouldn't have to sharpen my tools. Clamping the piece to a table with a C-clamp would protect me from cutting myself, he said. Later, when it came to painting my first carving, a friend of mine who was an artist suggested I use acrylics, so that is what I did.

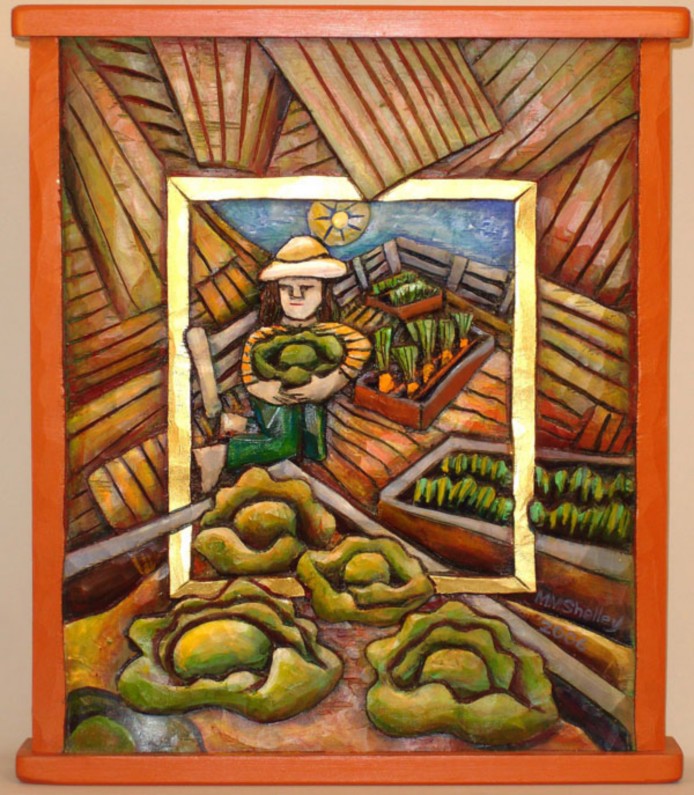

I use white pine and acrylics to this day. I've advanced to gold leaf in the inner frame (this began in 1990, when I went out of the sign-carving business and had plenty of gold leaf on hand), regular carving chisels, and a mallet. My father hand-filed a metal stamp for punching my initials "M.S." onto each completed piece. When I began to use my full name (Mary Michael Shelley) so I wouldn't be confused with Mary Shelley, the writer of Frankenstein, he filed me a new stamp with the initials "M.M.S."

In the early days, when I was teaching myself to carve, people would ask me to do carved signs, because people always ask artists to do signs. It all started out simply: simple pictures, simple signs. To get better at signs I read sign-making magazines, particularly the how-to articles about carving goldleafed, incised letters on wooden signs. The better I got at carpentry-I had advanced to finish work- the better I got at carving, and vice versa. The skills I was building with carpentry and sign-making advanced my ability to make more complex wooden pictures. As I drew more, I got better at drawing, as well, but I feel my basic style of drawing and choice of subject matter has stayed much the same over the thirty-five years I've been working.

About 1976 I made a connection with Jay Johnson's America's Folk Heritage Gallery in New York City, and I continued with that gallery until about 1990, when the gallery closed after Jay's death. Jay was an incredible mentor and a good friend. I miss him still. Although I've had other galleries since that time, once Jay died I began to sell my work on my own through craft fairs, the Ithaca Farmers' Market, and the Internet.

I've always had a day job. I became a parent in the mid-1980s, so I needed a steady income. For roughly fourteen years I worked as a sign-carver, carpenter, housepainter, whatever-and on the side I made my carved pictures. After the birth of my children and Jay's death, I went back to school to get a master's degree in social work. I have been a psychotherapist since the early 1990s.

I come from a mix of German, Irish, English, and Pennsylvania Dutch stock. My ancestors emigrated to America in the 1850s and earlier. The Shelley (paternal) side of the family has been here since Jamestown, but is distantly related to Percy Bysshe and Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley. People in my family have always been good with their hands. My paternal great-grandfather was an industrious German-American toolmaker and inventor, who lost a finger in a work incident. He lived in East Orange, New Jersey, and held a patent for the automobile windshield and push-button umbrella. My maternal grandmother was an artist, with her own wood shop and studio in her house. Through her I inherited many hand tools and a workbench that had passed down to her from her father, a tile layer, and his family, many of whom were carpenters. As a young child I used to do projects with her in her shop. When I was a young adult she'd take me there, point out a specific tool that had been in the family, and say, "When I die, you make sure to take this!"

As far as thinking of myself as an artist, my father was always a source of inspiration. After he gave up farming and began to work as a commercial artist, I loved to visit his studio at our farm. He gave me small jobs to do, like sweeping up or coloring in backgrounds to cartoons he had drawn. Much later in his life, he took to making carved pictures, repairing clocks and patent models, and even writing a book on New England tower clocks. He died in 2008. His advice and example were invaluable to me throughout my career.

I came from a family of artists, and I was driven to find my own means of expression. It's an honor to come from a long line of creative, inventive, and industrious people who were good with their hands. I take pride in my skills and being able to create a handmade product that will survive long past my lifetime. I hope to inspire others to carve and paint wooden pictures. For the past twenty-two years, I have demonstrated wood-carving on summer Saturdays at the Ithaca Farmers' Market. Many children come to watch me, and I wonder whether some of them will eventually try their hand at carving.

Although I've done many pictures of diners, sailing, and dream images, the barn is a favorite subject that fills me with the pleasure of visiting an old friend. My barn pictures carry layers of meanings, like Russian nesting dolls. It's thinking about these layers that keeps me going through long and solitary hours of carving in my studio, a renovated two-car garage located in back of my house.

One layer of meaning is simple: making a barn picture brings back pleasant memories. As a child I played in and around barns, not only in our own barn but in the barns of our Mennonite neighbors. Another layer is recording something from my life-the Kilroy, "I was here" theme. For example, I do some of my own farming. I've been a vegetable gardener for years. I am proud to say I raised my best bumper crop of cabbages last year.

The final layer is an emotional one, impossible to express, but I'll try. This theme began to take shape for me in the 1970s, and evolved out of a mix of emotions related to my experiences as a woman, the Equal Rights Amendment not passing, later on becoming a parent, Jay's death, and beginning to work as a psychotherapist. The theme relates to nurturing and serving, the endlessness of tasks, and human suffering (in the Buddhist sense). This theme comes out in my barn pictures, particularly the ones with cows and farmers. My cows are looking with strong feeling out of the picture. They wait to be milked-it's painful to have a full milk bag-and fed. They're cold and unhappy, but they're also enduring. Their needs are endless, continuous. Meanwhile, the farmers scurry about overwhelmed and overworked. They carry a heavy bucket as a symbol for their tasks. They're doing their best, but they can't keep up with farm chores. In both of these pieces it's winter. The skies are alive, active, and moving, reflecting my feelings about aging, about being just a small person in a large universe. The barn stands central, strong, and steady, a backdrop for the action.

So it seems that, in the end, my barn pictures are about me and making sense of the events of my life. I am the cows, the farmers, and the barn-and the skies are my moods.

Click here to download a PDF of this article.